Cogs, Balance Springs and Pistons

Did you know that there are several “Swiss watch connections” with regards to automobiles? Discounting, of course, the watches most automobile dealers have, resplendent with their corporate logos emblazoned on their faces. These timepieces which are usually displayed in automotive showrooms or service centers, are sold along with the stainless steel coffee mugs, jackets, pocket- knives, golf paraphernalia, etc.

No, what I’m referring to is the finely crafted Swiss watches, meticulously created with the utmost care and attention to each minute detail. And just like their automotive counterparts, the result is a symphony of design, art, function and precision.

The Huguenot artisans, many who were watchmakers, left France after King Charles IX massacred several thousand Protestants in 1572. They emigrated to the Calvinist bastion of Geneva, where their arrival gave birth to the watchmaking art for which this city would be renowned. Geneva already had a strong tradition of guilds inherited from the Middle Ages and in 1601 Genevan and French watchmakers who already possessed citizen status, united to form a single guild.

These Horologers designed and manufactured each mechanical part for their watches, and assembled them to create a symphony of cogs, levers, springs and escapements, that was truly an awesome sight to behold. The consequence of this labor of love was not only a precision instrument for telling time, but an extremely intricate and beautiful work of art as well.

One of the most prestigious Swiss watch brands of all time, Patek Philippe, produced a number of innovative models, starting in 1839. Their watches included the first to have a “free” mainspring and an independent second hand. The company’s aim was to produce the finest watches in the world.

Their goal was met, as the company, over the next few years, won more than 500 international awards. That was followed by an order from Queen Victoria, which led to the courts of Europe. Their clients included three popes. In 1851 the company was registered as Patek Philippe & Co. The watchmaker exhibited in Paris, a tiny watch the diameter of only 8.26mm, which was the smallest at that time. In 1868 the design was modified to make a timepiece for Countess Kocewicz. This was the world’s first wristwatch, but it took Patek Philippe another 50 years to manufacture a commercially viable version.

Some of the firm’s inventions were a double chronograph, with sweep seconds, a perpetual calendar mechanism, and an improved regulator. All these developments required much handwork, and in 1865 the total output was less than 2,500 pieces a year.

After the death of the two founders at the end of the 19th century, some of the company’s initiative seemed to die as well. Only in the 1920s did the first perpetual calendar wristwatch and the introduction of a man’s wrist chronograph watch result in a burst of creative activity.

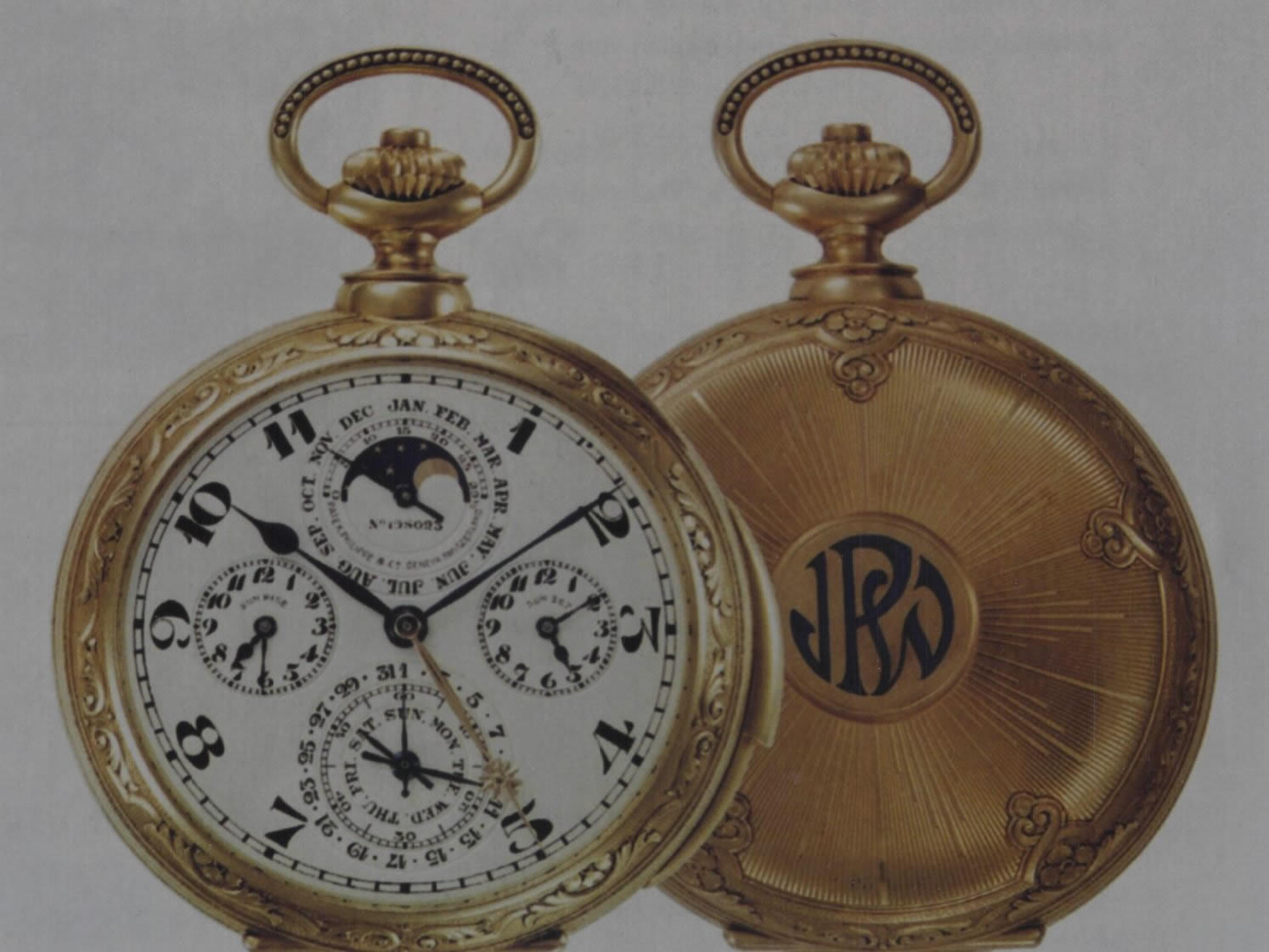

James Ward Packard, of Packard Motor Car Company fame, whose celebrated cars were to become synonymous with Hollywood stars, jazz musicians and sports celebrities, commissioned Patek Philippe to build two ultra-complicated pocket watches. The first, with sixteen complications, was delivered to him in 1916, and the second, with ten, was delivered in 1927. In fact, James Packard and New York financier Henry Graves Jr. had a long-standing competition, each vying to own the timepiece with the most complications. A complication is a mechanical function in addition to the hours, minutes and seconds. Henry Graves Jr. won with the world’s most complicated pocket watch delivered to him in 1933. This timepiece had twenty-four complications.

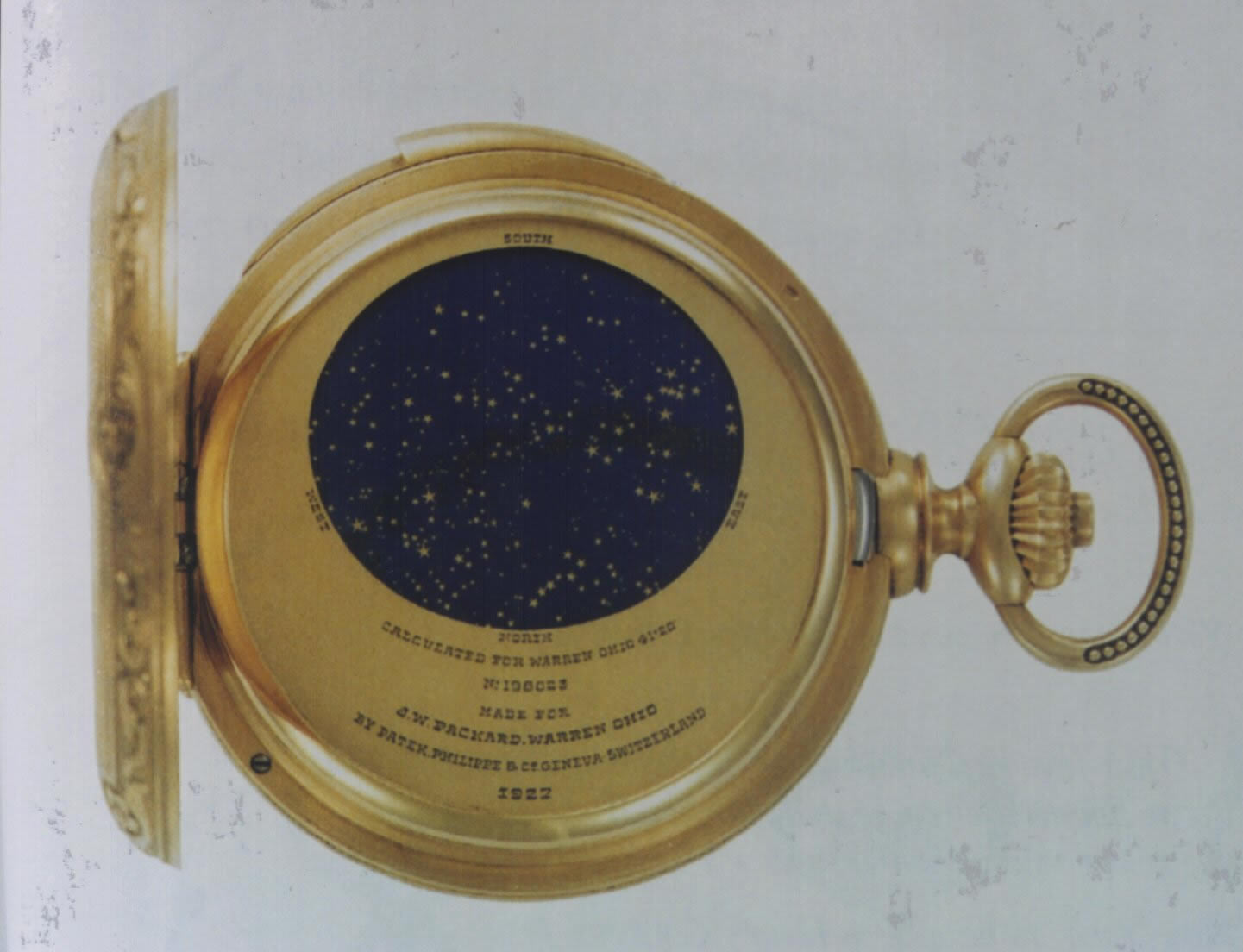

Of the two watches built for Packard, the most famous was the latter model. It took six years to make, and was completed a year before his death. This gold enamel open-faced pocket watch, numbered 198023, was keyless, and had ten complications. There was a minute repeater with three gongs, perpetual calendar with moon phases, times of sunrise and sunset, and included a rotating celestial chart with 500 stars, representing a view of the sky over Packard’s house in Ohio. The watch cost him $16,000. This particular timepiece was re-purchased by Patek Philippe in the late 1990s for their museum, for a princely sum of $2 million!

Tag Heuer, is another Swiss watch manufacturer with a passion for automobiles, especially racetracks and racing legends. Founder Edouard Heuer, was a fanatic for precision. When he began his workshop, based in Marin, Switzerland, in 1860, his aim was to take time measurement to greater heights. Since that time this avant-garde company has been on the leading edge of watchmaking technology. Some of the company’s key milestones include: the first patent for a chronograph mechanism in 1882, the first chronograph (Micrograph) measuring 100th of a second in 1916, the first automatic chronograph with a microrotor in 1969, called the Monaco, the first analog display quartz chronograph built in 1983 and the 1998 launch of the Kirium Ti5 in grade 5 titanium and carbon fiber. Heuer wrote some of the most prolific chapters in watchmaking history. For 140 years, the company has confirmed its’ initial goal, which is to produce watches that push the frontiers of precision, reliability and aesthetics.

Among the company’s many impressive accomplishments was developing and producing the first dashboard stopwatch for racing cars in 1933, called the Autavia.

The Targa Florio was one of the first road races, created in 1906, fought on the

Pebbled asphalt of Sicily. This race played host to the world’s most sophisticated cars and greatest racing legends before taking its final bow in 1973.

In the 1950’s Heuer created the Targa Florio Chronograph, with circular steel case with a fluted bezel. The black dial and rounded numbers, with two easily read counters, featured permanent seconds and minutes.

Many racing heroes attained glory at the Targa Florio, without actually winning the event. One of those was five times Formula 1 world champion, Juan-Manuel Fangio, who attempted the challenge in 1953 and 1955 with Mercedes. On his wrist was the Targa Florio Chronograph.

In 1964, Jack Heuer paid a connoisseur’s tribute to the “Carrera Panamericana Mexico” road race of the 1950s, by launching the newly developed chronograph from his father’s workshops in Switzerland and calling it “Carrera.” This Mexican odyssey was created in 1950 to celebrate the completion of the Panamerican highway linking the two hemispheres, the North and South, Alaska and Tierra del Fuego. It disappeared after only five years. This grueling race comprised of eight stages, and 3,113 kilometers of frenzied driving over a bridge of abrasive tarmac, sharp stones and red dust stretching under the watchful eye of the Popocatepetl and Orizaba volcanoes, from the North American border to the limits of Guatemala. This feat of extreme endurance for both man and machine ranks in the same league as the Mille Miglia, the Le Mans 24 hours and the Targa Florio. The unusual Heuer Carrera commemorating this mythical race featured a sloping surface around the dial rim, used for the graduated 1/5th of a second scale.

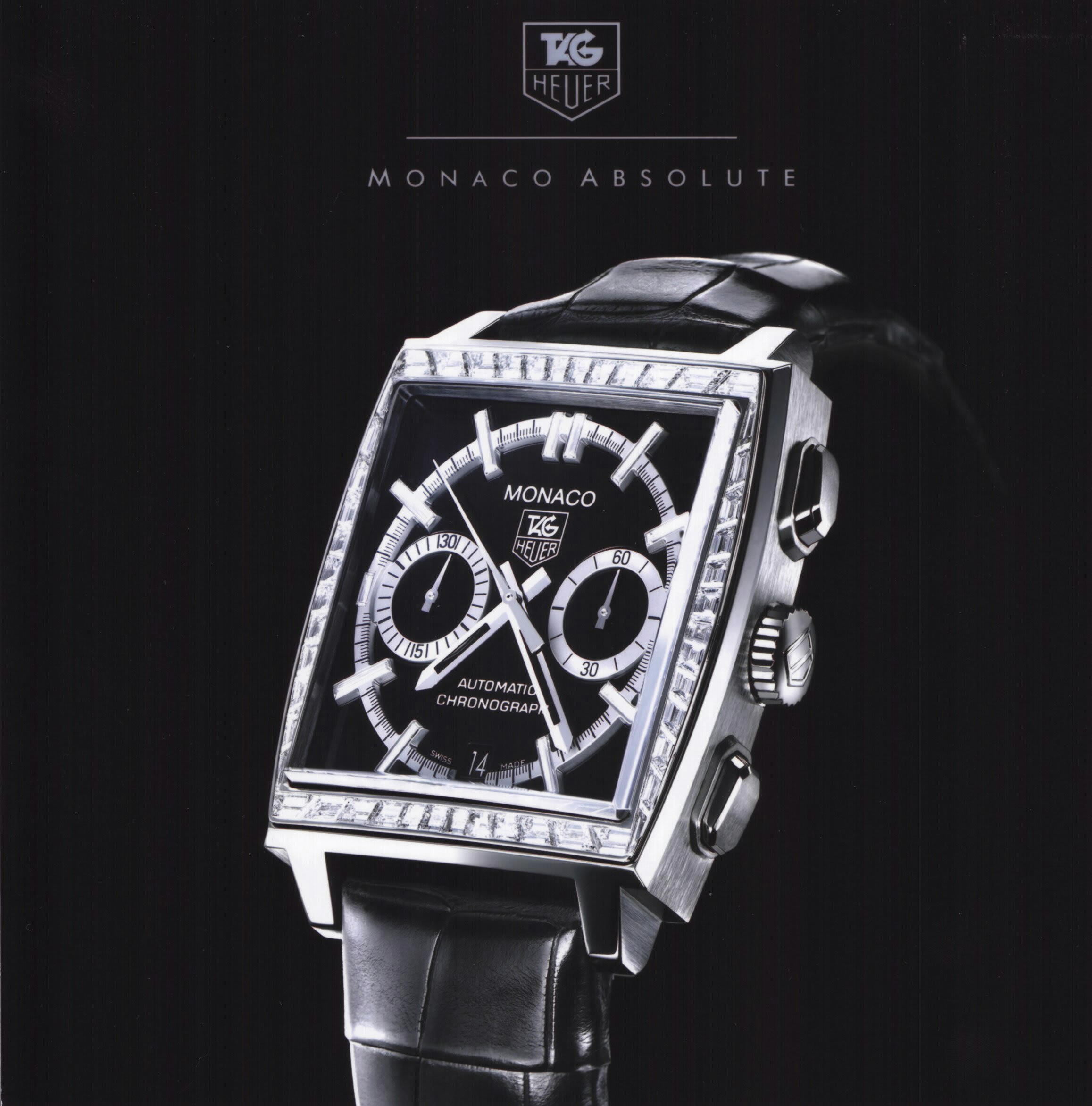

The Monaco, the watch that revolutionized the watchmaking world in 1969, the first automatic chronometer with microrotor, and fitted with a square watertight case, was worn by the Swiss Le Mans driver Jo Siffert. It was Siffert who trained actor, Steve McQueen for the greatest car film ever made, entitled Le Mans. Although not an immediate hit when the film was made in 1970, McQueen, more than most mere mortals and movie stars, actually drove the cars, did the stunts and took the risks. He even wore the same driving suit and colors as Siffert, as well as the same Heuer Monaco Chronograph. As a result of that film, the Monaco suddenly became the most coveted men’s watch on the market.

In 1971-79 Heuer became the official timekeeper for Scuderia Ferrari in Formula One racing. Since 1992, Tag Heuer (Heuer joined the Techniques d’Avant-Garde group (TAG) in 1985 to become Tag Heuer) has been the official timekeeper of the F.I.A. Formula One-World Championships.

Formula One racing has been one of the cornerstones of Tag Heuer history, partnering with the most prestigious racing teams like Ferrari and McLaren, and drivers like Coulthard, Siffert, Senna, Prost, etc. These events have inspired the company with making breakthroughs in technological developments in using new materials for their watches, with increasing precision and reliability of their products. As with the automobile industry, retro models are back, like the Mini, Beetle and T-bird. Tag Heuer has reintroduced their Carrera, Monaco, Monza and Targa Florio classics.

Today Tag Heuer continues to be the official timekeeper of the 2002 Formula One Championship, mastering the time of the 24 cars competing in 1/1000th of a second accuracy.

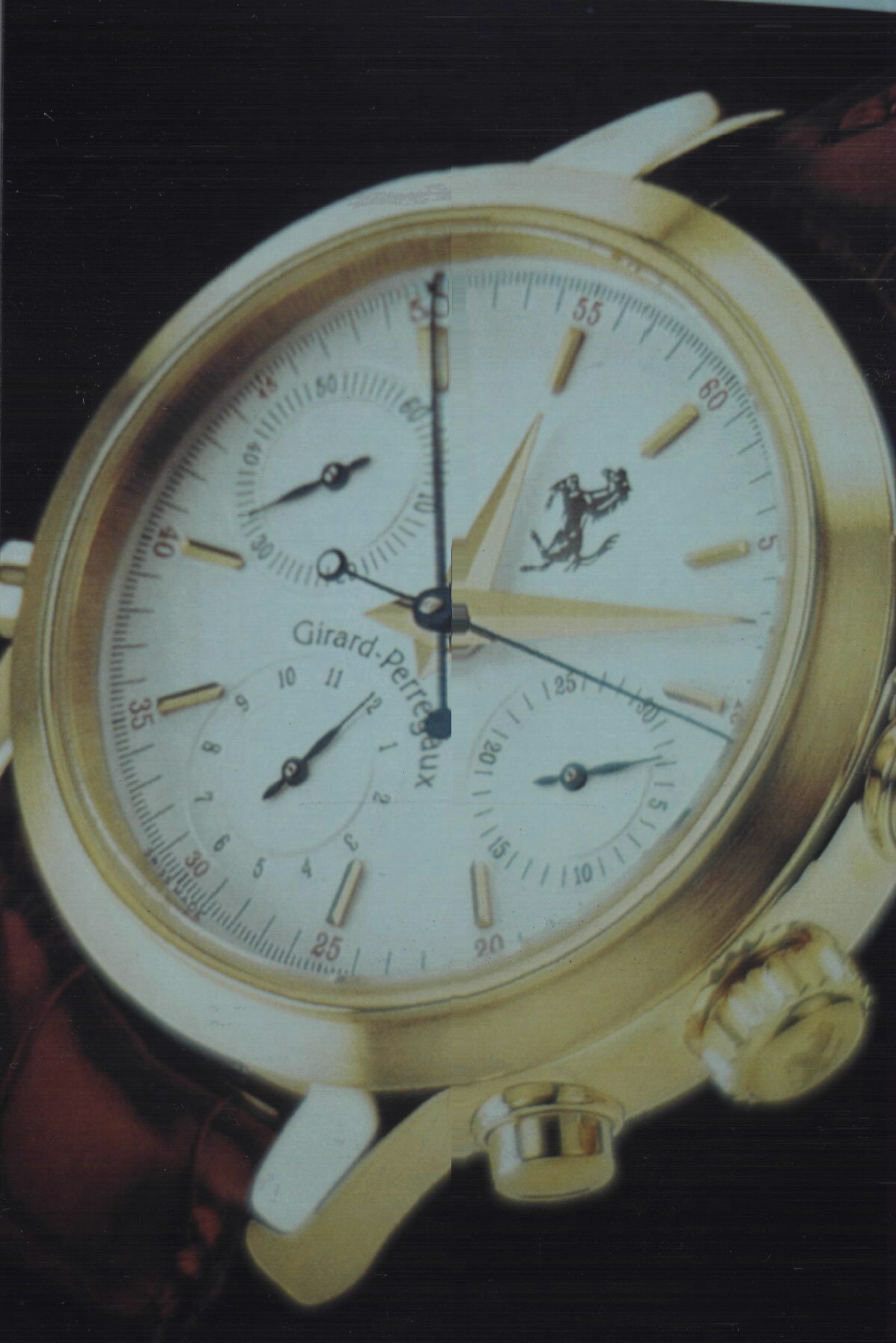

Lastly, here is one final example of a Swiss watchmaker partnering with an automobile manufacturer. In 1993, the Italian car manufacturer Ferrari decided to launch a prestigious wristwatch collection. The president of Ferrari inquired of his good friend and racing driver Luigi Macaluso, who was also president of Girard Perregaux if they could partner on this venture. The result was a sport chronograph series with the Ferrari prancing horse logo painted on the white or yellow dial.

This historic and important Swiss watch company can trace its’ origins back to 1791 in Geneva. Jean Francois Bautte created two beautiful watches that resulted in his employer Jacques Dauphin, to make him a partner By 1830, his firm was employing 300 workers and its’ products – the watch movements, cases, dials and jeweled watches were well known and highly regarded. Baute specialized in very thin watches, which resulted in him attracting many rich and important clients. In 1837 Jean Francois Bautte died, leaving the firm to his son. The company went through a variety of name changes, as it passed down to various family members, until Constant Girard Gallet inherited the company.

Gallet and his brother Numa founded a watch company in La Chaux-de-Fonds (near Geneva) in 1852. Two years later Girard Gallet married Marie Perregaux, who was also from a watch making family. It was then that the firm was renamed Girard-Perregaux.

In 1850 Constant Girard designed a chronometer design incorporating three straight bridges with a tourbillon (mobile cage which holds the escapement device of a mechanical watch movement and revolves, usually every sixty seconds, to conquer the effect of gravity on the running mechanism of the watch escapement. This design brought him immediate fame and he won a Gold Medal at the Paris World Fair in 1855. In 1867 the company decided to make the bridges out of gold, and won an award at the Paris Exposition in the same year and again in 1889. In 1901 it was deemed too perfect to compete.

In 1897 it produced an order of 2000 of the new “wristwatches”, the world’s first mass-produced ones, for the German Navy and was a great success.

In 1957, Girard-Perregaux patented a device, which allowed for very flat automatic movements, with increasingly high frequency (36,000 vibrations per hour).

Since 1982, the company has delved into their past and have resurrected the complicated pocket watch movement that was designed by Constant Girard in 1850.

Twenty examples of this watch were produced, identical in every way to the original. Because it took eight months to produce each watch, it is not surprising that the last of this series wasn’t completed until 1990. Since then, the company created a new wristwatch design based on the Three Bridges.

The Girard-Perregaux Ferrari collection started with a split-second chronograph, mainly in 18-carat white gold on the strap. Later, a stainless-steel automatic chronograph with a flyback hand and date was added. This was the company’s best-selling sports line.

In July 1996, the POUR FERRARI F50 wristwatch was launched, commemorating Ferrari’s 50th anniversary. The launch was an elaborate affair at La Chaux-de-Fonds, with a display of 127 classic Ferraris. What a lovely sight!

The next time you see a timepiece with name of a car manufacturer adorning the face, check to see if there is a history behind the watch manufacturer that may connect the marque. Who knows, it may be a priceless collectible.