Ostracized, Dispossessed and Uprooted…the fate of Japanese Canadians during World War II

Florence Kabayama, an 8-year-old Japanese-Canadian girl was living in the remote and isolated west coast British Columbian town of Ocean Falls. Life was good here during the late 1930s and early ‘40s. She lived in one of the homes amongst other Japanese families that formed their community, on the steep hillside across from the bay from the community’s chief employer, the pulp and paper mill. The Japanese families lived in their own area on the steep hillside while the Chinese community resided below them. “I remember the steep wooden steps that led up to our homes.” Florence recalled.

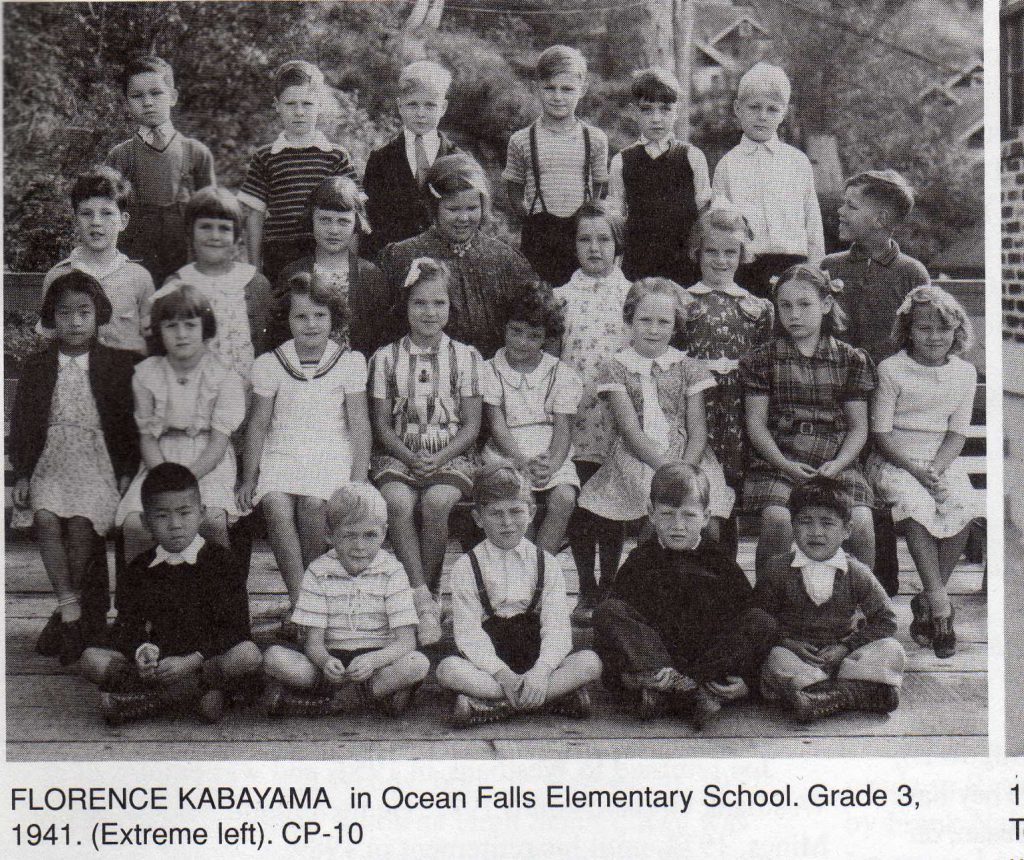

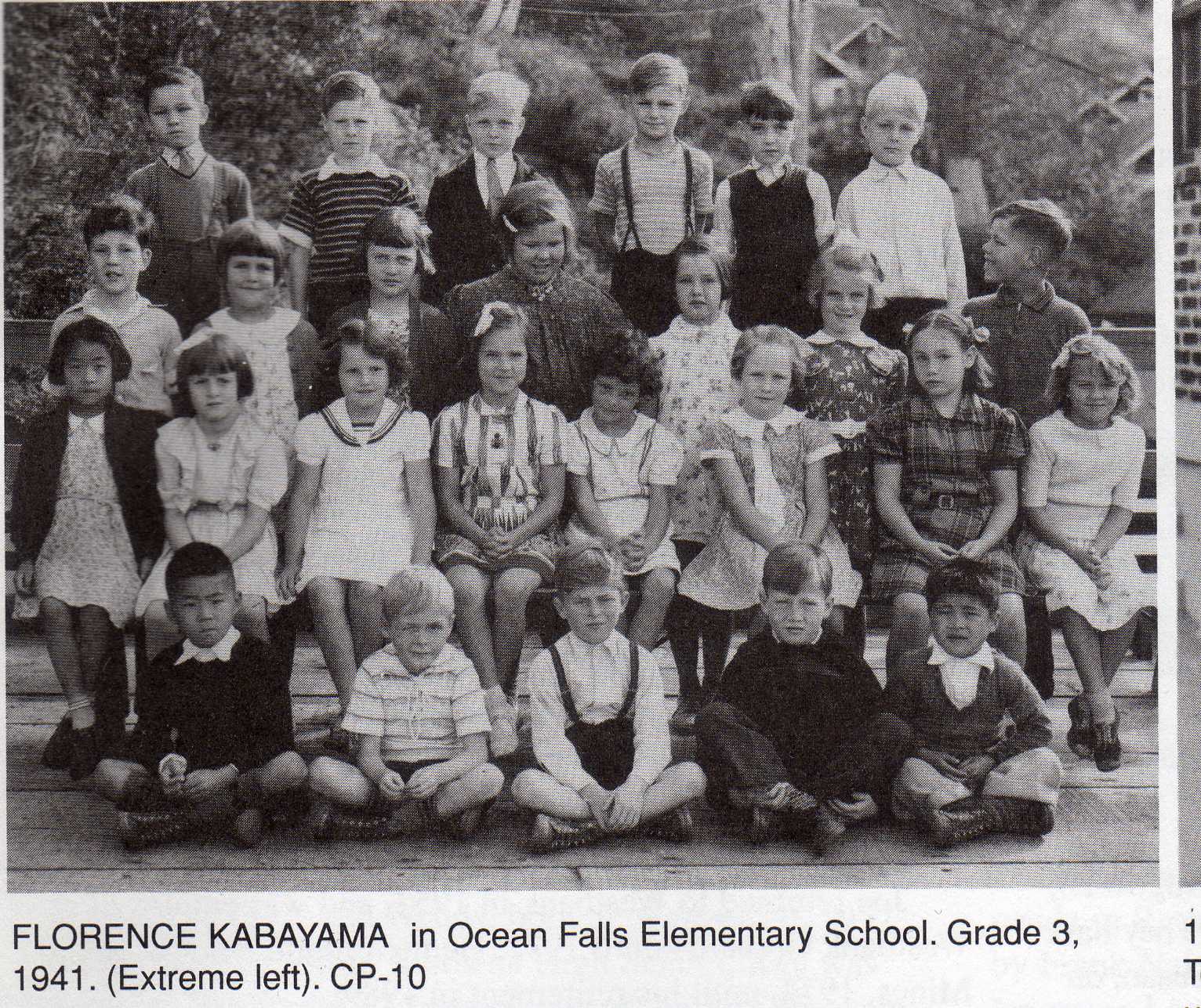

Florence attended Ocean Falls Elementary School and was the only Japanese-Canadian student left in her class when all the other Japanese families left. One poignant memory for Florence occurred when her teacher called her a stupid Jap. That left an indelible impression on the young girl that she remembers to this day. Florence never told her mother about the demeaning incident.

No one owned a car or truck in Ocean Falls. The milkman delivered glass bottles of milk to the families with a horse and wagon and another gentleman used a horse and wagon to deliver blocks of ice for the families’ iceboxes.

Florence fondly recalls the Japanese family picnics as happy experiences. At one of these picnics however, Florence, seven or eight at the time, waded out into the bay and the current swept her out over her head. As she could not swim, she panicked and called out for help. Fortunately, someone came to her rescue and pulled her back to shore. As a result of that traumatic incident, Florence had a lifelong fear of water and never learned to swim.

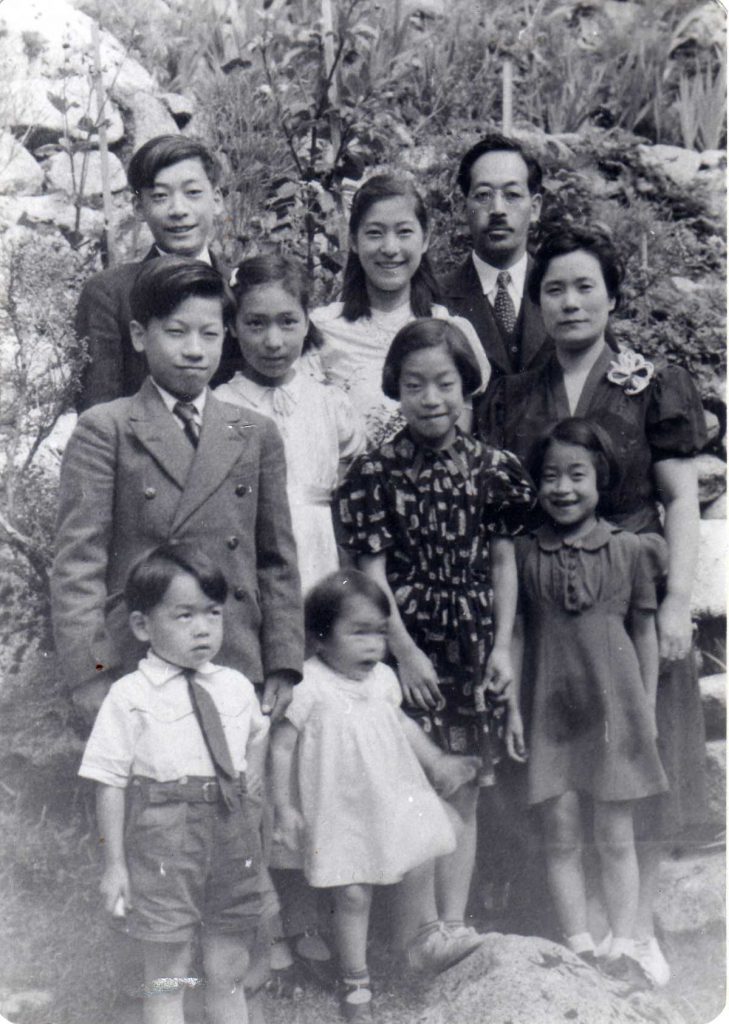

Her parents Jun, who was a Christian minister, and her mother Maki, along with their three children, Koko (Mary), Michiomi (Abraham) and Yoshiomi (Ezekiel) left Japan in September 1929 to cross the Pacific Ocean to Canada. Jun was called to pastor the Japanese United Church in the remote B.C. coastal community of Ocean Falls. The couple subsequently had five more children, Choko (Grace), Eiko (Gloria), Kaori (Florence), Taikan (Joseph) and Izumi (Lily).

The only way to leave or get to Ocean Falls was by ferry or boat. The Kabayama family led a happy peaceful life. However, that changed abruptly after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbour on December 7th, 1941. The federal government enacted ‘The War Measures Act”, thereby declaring that all Japanese people living in Canada were deemed to be aliens or enemies. Japanese-Canadians, those that were born in Canada, were stripped of their

citizenship, and their homes, businesses, vehicles and fishing boats were confiscated and sold. Furthermore, no Japanese or Japanese-Canadian person or persons were allowed within a 100 miles of the British Columbia Pacific coastline.

During this period of tribulation Jun offered assistance to their Japanese congregation members and neighbours as they packed up whatever belongings they were allowed to take with them on the ferry to Vancouver. “Before these families left, they banded together as my father led singing the hymn “May God be with you till we meet again.” This indelible memory has remained with Florence to this day.

February 23rd, 1942, was the day that the Kabayama family would leave their home in Ocean Falls. They would be the last Japanese family to leave their community. As the other Japanese families before them, their family boarded the ferry with only the possessions they could carry with them. Everything else, their furniture, appliances, beds, books, memorabilia, etc., were all left behind in their former home. “The piano that my mother played and my sisters learned to play on was one of the bigger items we had.” Florence recalled. “The natives would take the furniture, clothing and appliances, etc., that was left behind.” They would never return.

The ‘big boat’, as Florence described the ferry, was very cramped. When they docked at one of the ports for Vancouver, the family and other Japanese people were loaded onto the back of big trucks, possibly military trucks, and they were transported to Hastings Park. This property is where the Pacific National Exhibition (P.N.E.) was held each summer. Their temporary new home would now be in the livestock buildings.

“The first thing I saw when we arrived was the high fence that surrounded Hastings Park and the soldiers that patrolled the area.” Florence recalled. “They were guarding all the cars that had been confiscated from the

Japanese people. The cars were parked along the fence line and were so numerous that they surrounded the whole park!”

The men and women were separated and lived in separate areas. Jun and his two older sons, Michiomi and Yoshiomi lived in the male section, while

Maki, Koko, Choco, Eiko, Florence (Kaori), Lily and the youngest boy Joseph were directed to the female area. “The beds were all lined up along the inside perimeter of the horse building they resided in.” Florence remembered. Florence and her mom and siblings were fortunate enough to be housed in one of the horse stalls. That was a blessing as it gave them some privacy.

The horses’ water troughs were converted to toilets. For their meals, they lined up with their plates and received a plop of cabbage and potatoes or other tasteless or barely indigestible gruel that was fed to them each day. When there was something off in the food, people got diarrhea. This was a common occurrence. Head Lice was also a big problem. Florence’s mother was very busy trying to get the lice out of her children’s hair with a special comb.

Life for the Kabayama family, along with all the other Japanese-Canadian families that were interred in Hastings Park was very difficult under the confined and unsanitary conditions that reeked of cattle and horse dung. “I often think back to that time when my mother looked after the six of us.” Florence reminisced. “To this day I don’t know how she did it, but she persevered. Our health and welfare were her top priority.”

On August 5th, the family was ordered to leave Hastings Park. They were again loaded onto a truck that took them to the train station. There they boarded a train and headed east across the Rocky Mountains to Raymond, Alberta, a small farming community. Their new home was an old shed that was haphazardly prepared for the Kabayama family to live in. Their house

had no running water, so the water they required for cooking and bathing had to be collected with buckets from a nearby deep canal that had clean

water. Typical for the era, there was no toilet in the house, only an outhouse. The girls slept together in one of the bedrooms. “I remember sleeping with

my sisters, having to lie sideways in the bed in order to fit everyone in!” Florence vividly remembered.

The oppressing dry summer heat provided no relief, and they were plagued by hoards of mosquitoes from which there was no reprieve. During the winter months, as there was no insulation in the walls, the cook stove that was also the primary heating source for the home, was no match to keep out the bitter cold. The Kabayama family found the extremes of the Alberta weather intolerable compared to the milder weather they had experienced while living at the B.C. coastal town of Ocean Falls.

All members of the Kabayama family worked in the sugar beet fields for the resident farmer. “Once the farmer tilled the sugar beets out of the ground with the tractor pulling a tiller, we pulled the sugar beets by the leaves, banged them together to remove the dirt, cut off the leaves and stems with a large hooked knife.” Florence explained. “The beets were then stacked in piles on the field. We got paid a little money that helped our family buy some extra food and clothing. Sunday was our day off.”

Thankfully, the family later moved to a nicer house several miles down the road in another hamlet like Raymond. There was more room for their family with better bedrooms and a nicer kitchen.

Florence and her siblings had to walk a few miles, across fields to get to school. “In the spring we wore gum boots as we trudged through the sticky mud.” Florence continued. “In the winter months we used the same gum boots to trek through the deep snow.”

Meanwhile, Florence’s father bicycled throughout the region, visiting families that were members of the Japanese United Church as well as other Japanese people. He would make house visits, have Bible studies and conduct home services for families that got together. At times he would stay overnight before setting out for home the next morning. “My father would

travel up to 20 miles to visit these families!” Exclaimed Florence. “I remembered him coming home after a winter family visit with his mustache

covered in white icicles! Eventually, the congregation provided Jun with a car to make those visits. However, that move came with its’ challenges. As he had never had a car before, he had to learn how to drive. During the winter, Jun often drove off the road into a ditch near their home. He would summon the help from his sons to push the car out so he would be on his way again. There were also mechanical problems that came up with the car that were unfamiliar to him. His sons and friends would come to the rescue to try and solve the minor problems.

There were good times to be experienced by the Kabayama family and other Japanese families too. Japanese families gathered at the local community hall for dances. “The boys lived for the lunch boxes that the girls made for them.” Florence fondly remembered. “There was an auction for the lunch boxes and the boys that had the highest bids would be partners with those girls that made those lunch boxes, for the dance that night. The money that those boys paid for those lunch boxes went to pay for the hall rental.” Florence continued. “Those dances created some great memories for us during the war years, and they helped keep our spirits up!”

Jun was later called to minister a Japanese United Church in Lethbridge, Alberta. He also ministered to the Japanese families in the neighbouring communities of Taber and Pincher Creek. The family would live there until the Canadian War Measures Act was rescinded, allowing them to regain their freedoms.

In the opinion of Florence Kabayama, there was one good thing that came out of the forced relocation of the Japanese and Japanese-Canadian people living within 100 miles from the British Columbia coastline. “This experience resulted in the Japanese peoples to explore and settle in various parts of Canada, rather than mostly living in a concentrated area on British Columbia’s lower mainland and on the west coast.” Florence summarized. “We integrated with our communities, and were involved in various aspects of community life. My sister went to Lamont Hospital in Alberta to become a nurse, and my other siblings and me received post secondary school

education, just like many other young Japanese-Canadians. In essence, we became truly Canadian.”

Jun was asked to pastor a Japanese United Church in the Okanagan Valley in the early 1950s. The Kabayama family moved back to British Columbia. Florence married Westbank resident Stan Taneda in 1955. They operated an orchard for many years, and the couple raised three boys, Chris, Philip and Todd.